A coin, which was found after the service in the bell bag of the parish church of St. Sebastian in Würselen, is one of the earliest historical testimonies about the history of the city of Würselen. A farmer might have found it plowing in his field, and, having considered it worthless because of the strange inscription, he spends it light hearted to the collection. However, it was not worthless, though of simple ore. Together with other findings, this coin, showing a portrait of the Roman emperor Valentinian I (364-375), gives evidence to the fact that the area of the city of Würselen was already inhabited in Roman times. Two Roman roads, the road from Malmedy via Aachen to Geilenkirchen-Heinsberg and a second road from Herzogenrath to Verlautenheide, intersect here. A third Roman road today forms the quarter boundary against Broichweiden.

![]() The name 'Mauerfeldchen' means 'wall-fields'. It were fields where old walls were found. The Roman camps located at the crossroads grew over time by enticing merchants, artisans and farmers quite randomly and without actual planning for larger settlements. It will have been like that in the case of Würselen. In any case, wall fragments and screed floor of a Roman villa were uncovered in the land parcel "Mauerfeldchen", clay pots, bowls and glass vessels were found in many places, and even remnants of a Roman brickyard were discovered in the quarter of Elchenrath.

The name 'Mauerfeldchen' means 'wall-fields'. It were fields where old walls were found. The Roman camps located at the crossroads grew over time by enticing merchants, artisans and farmers quite randomly and without actual planning for larger settlements. It will have been like that in the case of Würselen. In any case, wall fragments and screed floor of a Roman villa were uncovered in the land parcel "Mauerfeldchen", clay pots, bowls and glass vessels were found in many places, and even remnants of a Roman brickyard were discovered in the quarter of Elchenrath.

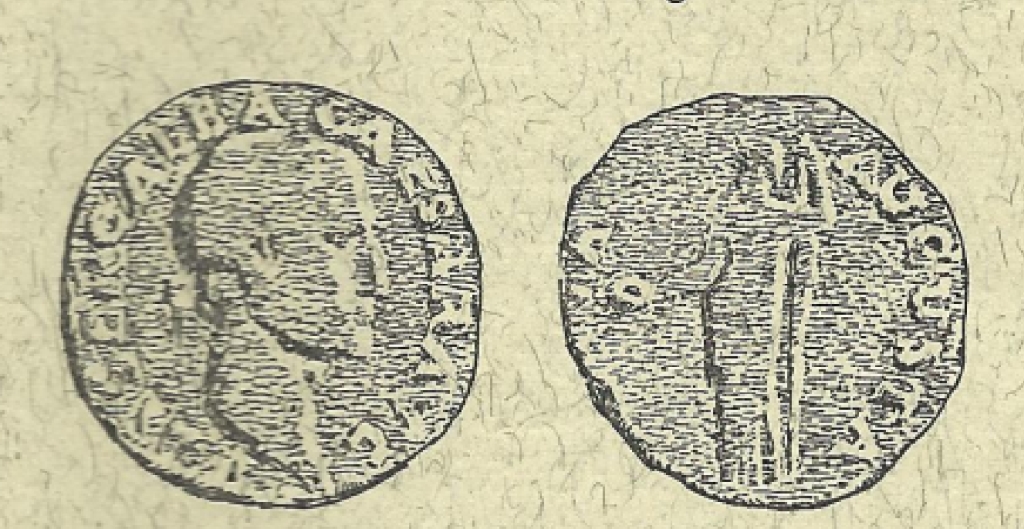

In addition to the find mentioned above, more Roman coins were found. They are named after the embossed head of each emperor and carefully registered according to their location:

Roman coins found in Würselen

Emperor Galba (68-69), silver, found in 1860 near the path to Scherberg at the so-called Judenstatt; Emperor Caligula (37-41), Ore, found 889 between Dobach and St. Jobs side of the Green Route

Emperor Constantine the Great (306-337), found in 1865 near the station Würselen, and finally the Valentinian coin already known to us Emperor Valentinian l, (364-375), ore, found in the bell bag of the parish church in Würselen.

Hence, the cultural history of today's city of Würselen, as far as it is handed down through historical testimonies, begins with the Romans. Although the Aachen area was already inhabited several millennia before the Roman era. It is known from finds that Stone Age people lived here around the year 2000 BC, but there are no indications of a human settlement in the area of Würselen from this time. Nevertheless, we should linger a bit on the older history of the Aachener Land.

The Stone Age was followed by the Bronze Age from about 1800 to 800 BC. They joined the oldest Iron Age and from about 500 BC to the younger Iron Age. At this time, the Gallo-Celts, originally from Asia, spread across the whole of Western Europe. The Celts, however, cannot enjoy their unrestricted possession for long. From the right side of the Rhine Germanic tribes invade the Gallo-Celtic borderland, among them a particularly warlike people, whose able-bodied men are excellent riders and who now settle in the Aachen area, the Eburones.

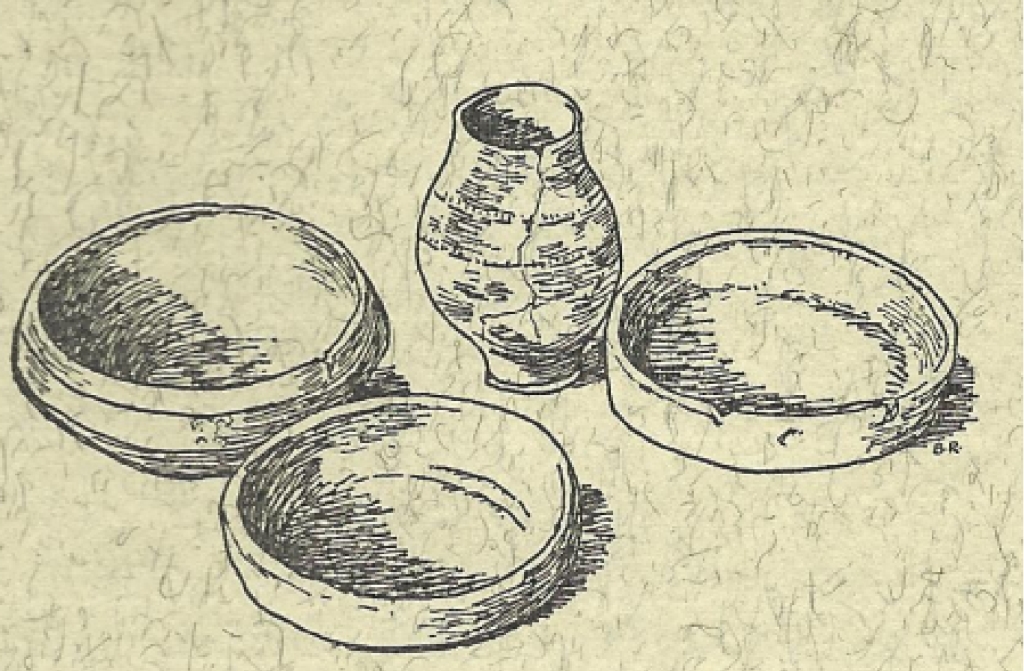

Potteries from a Germanic tomb near Kaisersruh

Eburones find a way to live together with the Celts. They sometimes even accept their ways of life, cultivate crops and livestock and forge intricate jewelry and weapons from their own iron. But when in the first century BC Roman legions conquered the country up to the river Rhine, the Eburones recollect their warlike past. In the year 57 BC, they fight and inflict great losses on the Roman army. In an uprising against the occupation from Rome fifteen Roman cohorts are destroyed in 54 BC, about 8,000 men. But the joy of this victory does not last long. Only a year later, Julius Caesar sets out on a campaign of revenge against the Eburones, where their villages and farms are burnt down and most of the inhabitants are killed. The extermination work is so thorough in the Aachen area that the Eburones no longer exist as its own ethnic group.

The Romans did not leave the devastated area uninhabited for long. They assigned the land west of the river Wurm to the Celtic tribes of the Segnier and Kondruser, while they settled the Ubier, a Germanic tribe of the lower Lahn, east of the worm. Already here the meaning of the river Wurm begins to emerge for later territorial claims: In all political and ecclesiastical divisions in the following centuries, the Wurm always formed the most important natural boundary.

This was already noticeable in the 5th century during the migration of peoples, when Frankish tribes invaded the Aachen area. The Ripuarian francs occupied the area east of the worm and mingled here with the Ubiern, while Salian Franks shared the area with the Kondrusern in Aachen itself and to the west of the river Wurm. To this day, linguists can identify the dividing line between the tribes in the various dialects.

This is the opportunity that a Germanic tribe from the right side of the Rhine has long been waiting for. From the land between the Rhine and the Weser, from the Westerwald, from the Sieg, from the Sauerland they come across the Rhine. Numerous settlements fall victim to them before the political and military rule of the Romans in the area of today's Aachen district finally collapses at the same time as the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476.

But the time of the Franconian empire is still far away. For now, for almost 500 years, the Romans dominated the left bank of the Rhine. After bloody wars of conquest and the consolidation of their rule began, also for the Aachen area a centuries-long peacetime, in which the native population learned a lot from the culturally high Romans. The Romans brought craft and agriculture to their heights, they developed mining for iron and calamine, perfected artistic pottery, and were the masters of the architecture; not only in the construction of houses, but also of roads, bridges and water pipes. In these centuries of secure, peaceful development, the settlement built on the site of today's town of Würselen will have gained momentum at the crossroads of the two Roman roads. Dangers of hostile neighbors were averted by the Roman occupation forces. Thus, nothing disturbed the picture of an unclouded peace, until in 416 Rome, which had been shattered by serious internal conflicts and threatened by external enemies, had to recall its troops from the occupied territories.

Please observe the copyright of the city of Würselen.

For more information see here.

Some comments and explanations have been added.Such information is presented as follows:

Comments and explanations go here.