The rule of the French did not last long. It ended in 1814, a year after Napoleon suffered his decisive defeat in the Battle of Leipzig. Nevertheless, after the French left, the old balance of power will not be restored. In 1815, after the decision of the Congress of Vienna, the Rhineland fell to Prussia.

The Prussian eagles appear on the council and municipal houses as a sign of the new national sovereignty. In the same year, the Prussian Rhineland were divided into the six administrative districts of Düsseldorf, Aachen, Cologne, Kleve, Koblenz and Trier. In 1816, the counties were set up and from then the municipality of Würselen belonged to the district of Aachen.

In many areas of the administration, the reforms introduced by the French have held their way, albeit in a modified form. This is most evident in the municipal administration, for which the French municipal constitution remains valid. It was not until 1845 that the Rhenish Municipal Order took its place. On 5 September 1817, the Aachen district council sworn in the former municipal secretary Sebastian Kind as mayor.

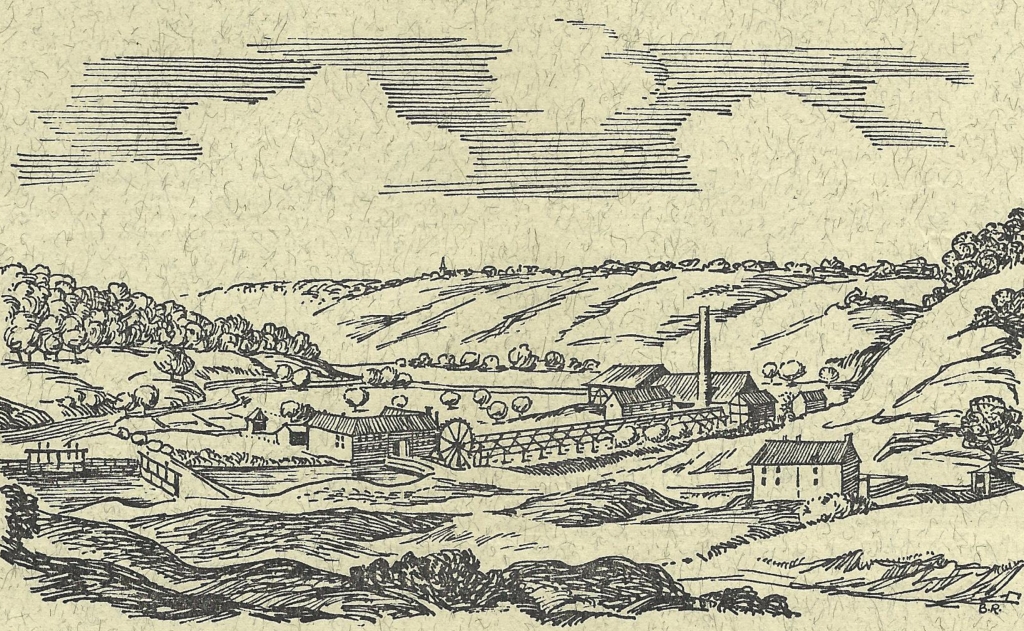

The old Teut pit in the Worm Valley (circa 1780)

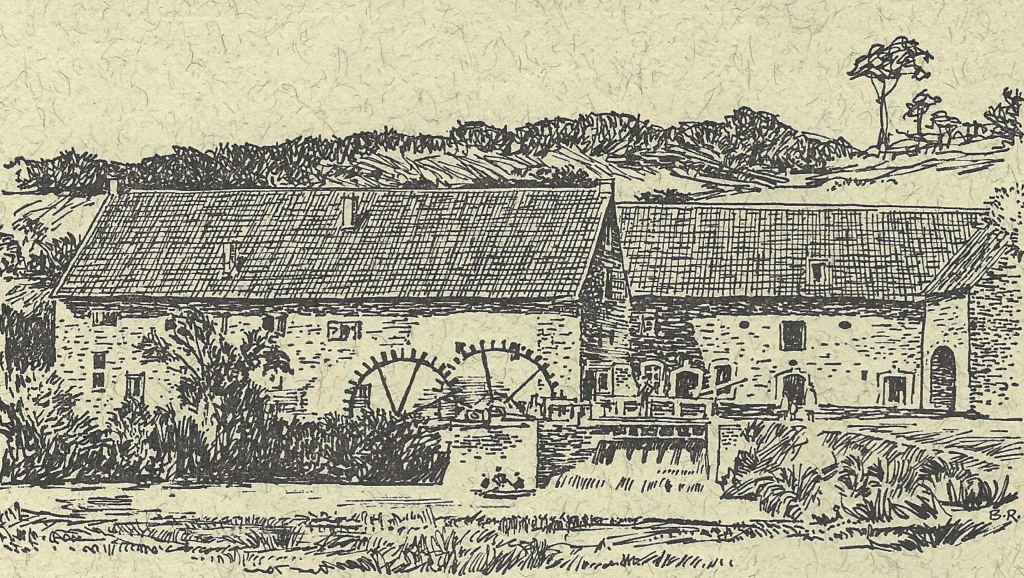

This act is so significant because, after a series of honorary mayors, Kind becomes the first professional mayor of the municipality. As the official residence, two old school rooms are available on the market. Everything quite small and modest, and you certainly can't blame the newly minted mayor if he ran his official business mostly from his apartment in Adamsmühle.

In 1823, 3648 citizens lived in the mayoralty of Würselen. The village of Würselen itself had a population of 340 around the same time. Their numbers grew slowly.

In 1845 there were only 358 inhabitants, the village consisted of 69 houses. In the general community, the number of residents had risen to 5464 by 1871, living in a total of 912 homes.

With the introduction of the Rhenish Municipal Code of 1843, the mayoral Würselen had a municipal council with 18 members. They had to deal with an unpleasant problem right at the start of their term: The government in Aachen did not want to confirm the mayor elected by the local council Ignoring the municipal council’s vote, Aachen appointed the mayor of Haaren as mayor of Würselen in personal union.

For more than 50 years, Haaren and Würselen were then managed in personal union, with the administration's seat in Haaren, even though Würselen was the larger and more important one of the two municipalities. In Würselen itself, in the house Markt 21, purchased as an administrative building, a room was set up as a municipal office only on the ground floor, where the mayor held a few hours of consultation on a weekly basis.

There was also a council meeting room in that house, a registry room, two arresting local and the housing of the prisoner keeper and another police officer. They were the only police force in Würselen in the middle of the 19th century.

Therefore, at the beginning of industrialization, Würselen was able to rely on its commercial tradition that has been developed over many hundred years. Especially in metal processing, the place had rich experiences. As early as 1650, there were six copper mills, in whose melting furnaces made of copper and calamine brass were extracted and hammered into sheets and plates.

Copper blacksmiths, the „Kofferschläger”, then took over the material and processed it into artistically high-ranking products that were shipped all over the world. In addition to the copper blacksmiths, the Würselen-based needles also had a world-wide reputation. Their products, which were smoothened and cut needles in the water mills on the river Wurm, were originally also made of brass.

However, coal mining became even more important than these two branches of trade for the further development of Würselen. The Mining in the Wurm area is one of the oldest in Europe. As early as the 12th century, the yearbooks of the monks of Klosterrath gives evidence of the coal-mining district along the river Wurm.

There is more infomation here.

Adamsmühle in the Wurm Valley after a photograph from 1896

From these early beginnings up to the French period, the Aachen Council, as the lord of the country, has secured a decisive influence on the coal-mining in the Würselen-based ‘Bergwerksfeld’. Those who wanted to extract coals in Würselen had to apply to the Aachen Council for the award, paid an enrolment fee and then received permission to exploit a coal leader with “Gang and Strang” (lifting hole and ducts) of course against corresponding levies to the city. Temporarily, the city of Aachen had even owned its own mine with the Teut mine in the Wurm Valley.

In its early days, coal extraction in the Wurm area took place almost exclusively in open-pit mining, as most coal seams reach out to the earth's surface. Later, several beneficiaries merged to form societies or small "unions" capable of cutting coal even underground in a larger style and with better tools. But as late as the 18th century there were no less than 69 "Kohlwerke" (coal mines) in the Würselen area! It was not until the 19th century that the first major concentration measures began.

The Unification Society for Coal Mining in the coal field along the river Wurm acquired the three most important Würselen pits called Gouley, Teut and Königsgrube one after the other, thus creating the precondition for an efficient mining industry in the age of industrialization. In 1907, the Unification Society merged into the Eschweiler Mines Association.

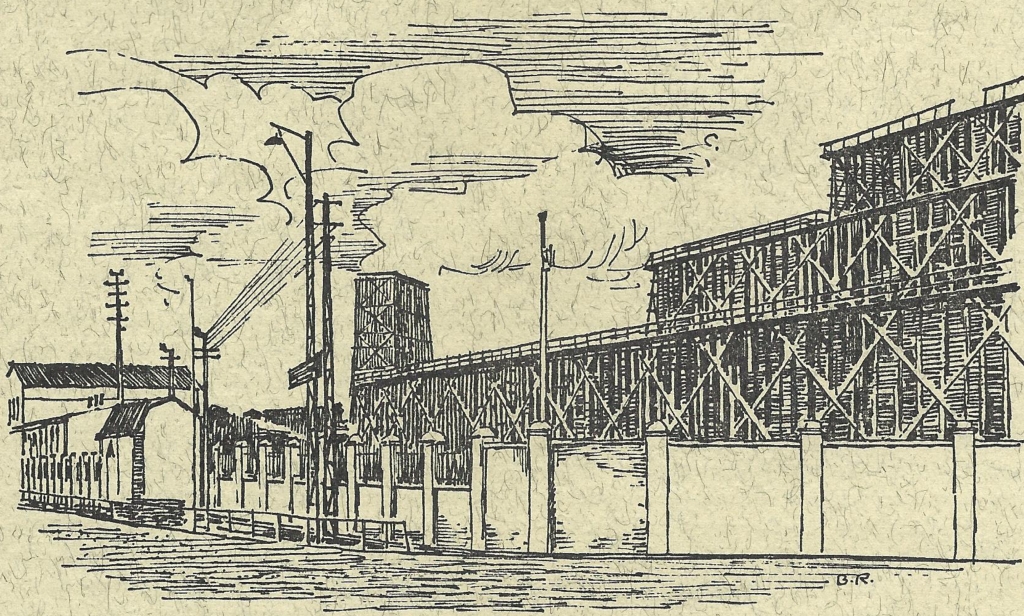

In the course of the 15th century, other important branches of trade in Würselen were settled in the existing sectors, among them works of the cloth industry, the electrical and chemical industries.

However, they not only brought joy to those responsible in the large community at the time: In the general pursuit of rapid growth and increased profitability that dominated the hectic early years of industrialization, the social problems all too easily were overlooked. Hence, taking care of the poor soon became a child of pain for the administration. A report, from 1856, states:

“The ‚Armenwesen‘ (poor relief, social care) is expanding in the community as a result of the increasing industrial establishments from year to year; Some of which damage the vitality and the health of the workers to a high degree; Some of which lead to an irregular way of life. Male and female children from the working class, which is predominant in Würselen at that time, can hardly wait for their dismissal from school, only to seek employment and earn money in factories or mines as soon as possible.

The value of money is not really noted because it is so easily won. Waste, drunkenness, etc. are an unavoidable consequence .... " The report also complains that poverty and the number of poor people is constantly increasing and that the subsidies to the fund for the poor are therefore increasing significantly.

Social legislation was not yet known. But as early as 1851, a support fund was set up to support factory workers in the event of illnesses in Würselen, whose contributions were funded by employers and employees in half. Workers received free medical treatment and medication. The revenue and expenses of the funding were estimated at around 1000 ‘Reichstaler’ per year.

With the growth of industrial enterprises, a lively construction activity had begun in Würselen. Often, 80 to 90 new houses were built in one year. Entire streets were newly developed, and since new districts spring up like mushrooms in neighboring Aachen, many workers from Würselen found employment in the construction industry. Wages rose rapidly, so that in 1865 the day wage for a henchman was 25 silver groschens - by then a lot of money.

But, as always with a stormy development, there were some who do not benefit. It was the farmers who lost more and more workers to industry and construction, and eventually had to move on to recruiting “guest workers”: Men and women from Holland who were willing to work in agriculture.

Once in the process of construction, people in Würselen no longer wanted to do without their own town hall. In 1904, on 11, June, the foundation stone was laid in the present town hall, but already eight years later it proved too small and had to be extended by a side wing.

The individual districts that were to be managed from this town hall had grown more and more together. On 9 November 1904, therefore, the government considered it necessary to impose the name Würselen as a uniform place designation to the villages of Bissen, Drisch, Elchenrath, Grevenberg, Haal, Morsbach, Oppen, Scherberg and Schweilbach, which already belonged to the district of the municipality of Würselen. This name also was applied to the hamlets of Dobach and Neuhaus as well as to the residential places at Duisburger Straße, Hochbrück, Kaisersruhe, Meiß, Teut and Strangenhäuschen.

Only in the places of residence Knopp, Pumpermühle, Teuterhof, Adamsmühle and Wolfsfurth were dispensed. They were allowed to keep their previous names because it was considered impossible due to the spatial distance that they would ever merge with the rest of the municipality.

At the same time, the individual streets of Würselen were given their street names, with emphasis on them: Keep the old village and hamlet designations.

The extraordinary name of the place “Kaisersruhe” (Emperor's resting place) - or far more often used “Kaisersruh” - dates back to an event in the autumn of 1818. At that time, the rulers of Prussia, Austria and Russia met in Aachen for a European "summit conference": the three-monarch congress. On it, the peace in Europe regained after the Napoleonic wars should also be secured for the future.

During the congressional breaks, Tsar Alexander made a penchant for a long ride into Aachen's vicinity – mostly incognito. One of them led him to the nearby Würselen. It was November 12, 1818, when he stopped at a country estate with his companion, a Russian officer. The incognito of the two "officers" was soon ventilated, and henceforth the place where the high lord chose to rest was called - Kaisersruh. By the way, with the most gracious approval of the tsar.

Plants of the Soda factory on Krefelder Straße, which was discontinued in 1929

Not only among themselves, the districts of Würselen had grown together in the 19th century, but also the neighboring communities had closer contact. This is what the railways have already made sure of. The first connection by rail was given to Würselen in 1875 with a railway line connecting the village with Aachen-Nord station. During this time, the station at Elchenrath was built. 1892 the Würselen-Kohlscheid railway line went into operation. A few years later, the small railway line was added between Aachen and Würselen, which was handed over to traffic on 22 August 1894.

At the turn of the 20th century Würselen offered the image of an up-and-coming community that had taken the path from pure agriculture to a commercial large-scale economy at an early stage, open to technological and industrial progress and in lively exchange with the neighboring communities and the city of Aachen.

The population had also been constantly upwards. In 1900, Würselen had a population of almost 10,000. They all firmly believed that nothing would stop the upswing of their place.

On June 28, 1914, the ominous shots of Sarajevo fell. The First World War began. The war and the subsequent occupation of the Rhineland by French and Belgian troops abruptly interrupted the development, which had begun so hopefully.

Please observe the copyright of the city of Würselen.

For more information see here.

Some comments and explanations have been added.Such information is presented as follows:

Comments and explanations go here.