The last years of the Second World War are the hardest that Würselen has ever had to survive in its many hundred-years lasting history. They begin with an almost uninterrupted succession of aviator alarms, in which numerous houses are destroyed and many people in Würselen are killed. In the large-scale attacks on the neighboring city of Aachen, Würselen is rarely spared. The population has been trained in air protection. At dusk all houses, street lights and vehicles must be blacked out. Air raid shelters are set up in the basements of the houses, the houses themselves connected by basement breakthroughs as escape routes. All basement holes have been given seals due to the risk of shell splinters. In addition, tunnels were created in the Sodaberg, at the Singerwerke, in Zechenhausstraße, Balbinastraße and Aachen Street; They should provide protection for the population against the bombs in airstrikes. But despite all these measures, there are repeated fatalities.

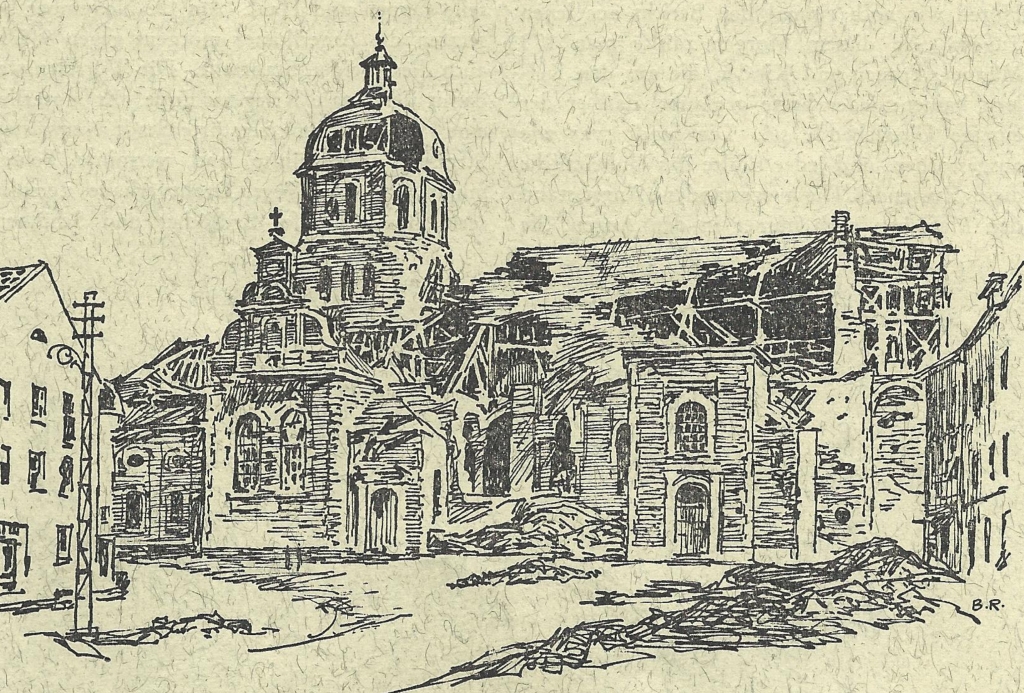

St. Sebastian Parish Church after World War II

On September 12, 1944, air raid warning is given for the last time. It is the 532nd warning, as a Würselen-based resident notes in a diary. However, this time, residents left behind in the city are vainly waiting for the ‘all-clear’ signal. It will never happen again. Instead, the next day the first grenades hit Würselen, the battle of advancing Americans for the city had begun. From now on, the Würselen area is under constant fire for three months.

The attack by American troops was primarily aimed at conquering Aachen. Until September 21, Aachen was encompassed from almost all sides. Only via the Krefelder and Jülicher Strasse there was still a loose connection to the hinterland, the "hose of Würselen". It was often mentioned in the war reports in those days, but it also shouldn't stay open for much longer. In the second battle for Aachen, which began on 2 October 1944, which includes fierce battles for Bardenberg and Würselen and the bunker positions there, the hose was brought in more and more until the latch position was no longer held on 16 October. Aachen was completely surrounded.

On 21. On October 10, the white flag appeared on the bunker of the Aachen Combat Commander: The German troops surrendered to the forces of the I. US Division.

In Würselen, little more than 1000 people had been left behind at that time, 1000 of the approximately 15000 regular inhabitants. All the others had been evacuated in part under coercive measures. Also evacuated was the city administration, which first moved to Stetternich in Jülich County and from there to Hennef on the river Sieg. One of their main tasks at that time was to answer the requests of citizens evacuated from Würselen, which arrived from all parts of Germany with questions on the fate of relatives.

But let us stay in Würselen with those who were neither to be moved by persuasion nor by threats to leave their homeland from the rolling up avalanche of war in order to bring themselves to safety. Their fate is described in a contemporary report:

"The population left in Würselen after all the tribulations, coercion and threats by the party men camped out in the cellars of their shot houses or in the tunnels. Some ‘basement communities’ had formed.

Hundreds of men and women had to spend day and night in the tunnels without interruption.

There it was almost always dark and humid. The water dripped from the walls and ceilings. The floor was wet. In some places, the water stood up a hand width. Almost no one could lie anymore. People had to stand or sit. The water supply was interrupted, as was the supply of light. You look at yourself with candles, as far as those were available.

The potato harvest could no longer be brought in due to the strong shelling and the risk of mines. Anyone who tried to bring potatoes home anyway did so at their own risk. Milk for the babies was hard to find.

The population lived on existing food supplies and the surrounding and wounded livestock, which was slaughtered and distributed. In this situation, food rations had to be restricted to the extreme. Only during the battle-free time – early in the morning, during lunchtime and in the evenings between 5 and 6 o 'clock it was possible to bring in water from an intact well.

Many who left their hiding place to draw fresh water had to pay their trials with injuries or even death. A sixteen-year-old girl was left with her head by shards of grenade while fetching water at the Knopp. The dead could often no longer be buried in the cemetery but were buried where the fate had befallen them. "

On the night of October 9, 1944, the first American tanks rolled through Gouleystraße and took Morsbach. Despite fierce resistance, the Americans also managed to occupy the nearby districts of Schweilbach and Scherberg. Aachener Straße and Krefelder Straße now formed the main battle line, where the frontline combat troops, separated only by a width of the roads, were opposite each other.

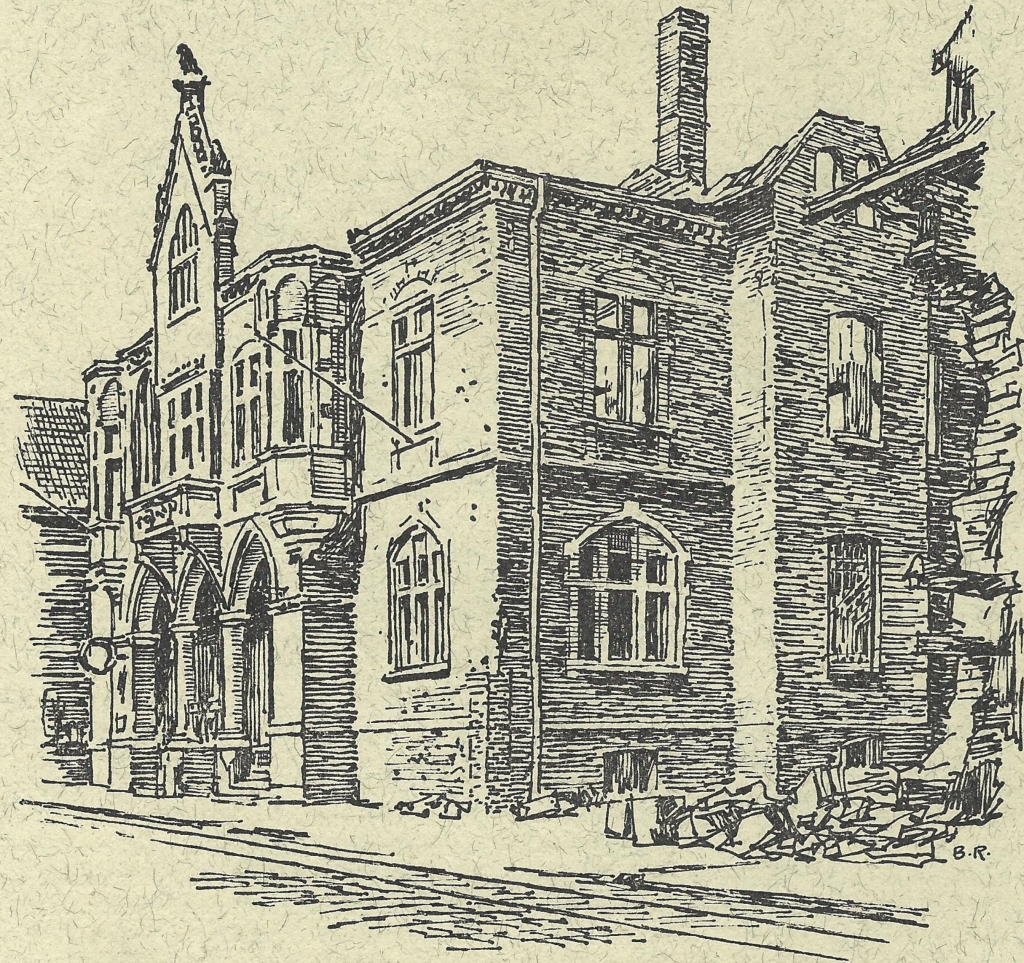

The destroyed town hall

On the German side, strong tank units were once again deployed to turn the situation. However, they failed to kick the Americans who answered the attacks with artillery fire from the occupied districts. On the other hand, The Americans are not recording any terrain gains in the battle for the center of Würselen, even though they had given heavy bombs to the city's core on October 18 to force a rapid progress of the operation.

For nearly six weeks, the front went through the middle of Würselen. On November 17, 1944, the Americans hit the decisive blow. The distraught, horror-paralyzed people who had survived the battle in the air raid shelters and tunnels so far had to endure a nearly three-hour drumfire.

It is estimated that 5000 to 6000 shells fell on the city center. The cringing of the tank chains mixed into the eerie silence that followed the shelling at the morning. The first American tanks, did not find any significant resistance, moving up to the railway line Neuhäuserstraße – Friedrichstraße. They conquered a city that had been turned into a grisly debris field by the weeks-long battles, where piles of debris and scree masses covered the streets, so that ploughs are deployed to carve a path for the tanks.

Let's listen again to the report from those days: "That morning there were 178 men, women and children who came out of the cellars. Each had believed he was the only survivor. The city was like extinct, and everyone felt the sinister of this state. The extinct fear was still in people's eyes. The six weeks in the forefront had witnessed everything that involved war and passed a tremendous nerve test. "

On the night of 17 to 18 November, the last German soldiers left the districts of Oppen and Haal. On November 18, the Americans also occupied these two parts of the city in the morning, in the day. For Würselen, total war was over. It left behind a 79 percent destroyed city, ravaged streets, agitated and mined fields, mine-infested paths, wire cages, fragmented tree stumps, earth holes and shooters digging - where a thriving city once stood.

Here, in fact, the history of Würselen ends, the history of a city, if one sees history as the representation of the past. Everything which happened in the last 25 years in Würselen from now and still happens is living presence, designed and experienced by all of us. But one day it too will be part of the history of this city. It is up to us, the citizens of a democratic state and a democratically administered city, how it will be written later.

Please observe the copyright of the city of Würselen.

For more information see here.

Some comments and explanations have been added.Such information is presented as follows:

Comments and explanations go here.